The Oxford English Dictionary defines serendipity as the “faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident”. Serendipitous was, indeed, my encounter with Jill Anholt‘s art installation Lines of Work. Jill Anholt is a visual artist based in Vancouver and involved in public art since 1998. She’s also an instructor at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver.

My encounter with Jill’s work happened on a sunny May afternoon. In those days I was working on my thesis, specifically on a chapter about the history of Vancouver’s digital and new media industries. While walking along Coal Harbour, the stretch of land going from Canada Place to Stanley Park, I decided to take a detour and explore the west-facing facade of the Vancouver Convention Centre.

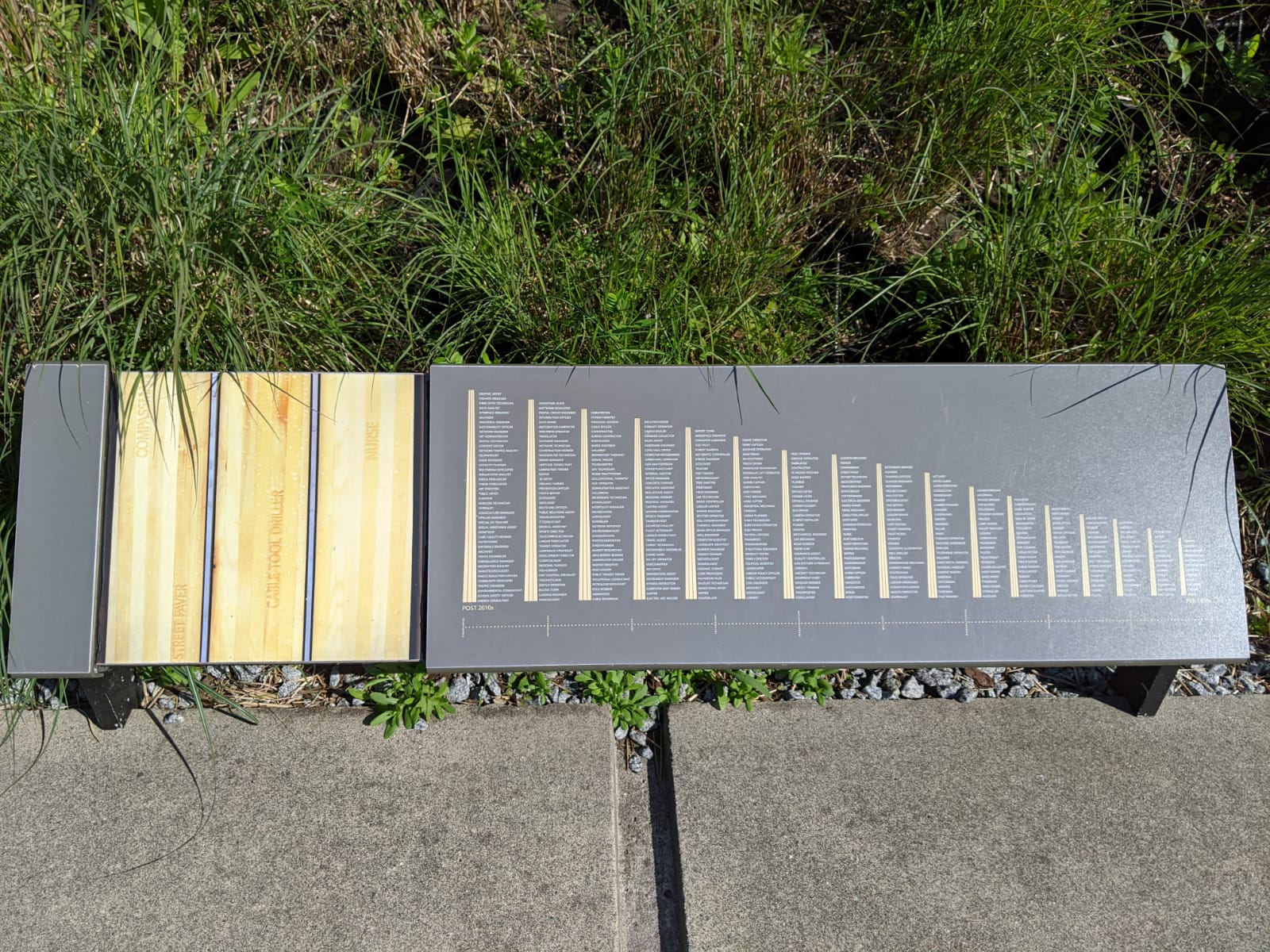

Along the pathway going from the seawall walk to Vancouver’s Olympic Cauldron, I discovered Anholt’s installation: a series of 17 wood elements representing the transformation of Vancouver’s workforce from 1850 to 2010. Curious about the project and the creative process behind it, I emailed Jill asking for an interview. What follows is a summary of our conversation. I hope you’ll enjoy it and, in case you happen to be around Vancouver, I invite you to visit Lines of work in person.

Alberto: Hi Jill and thank you for taking the time to talk to me today. To begin, I’d like to learn more about the genesis of this project. I read that it was commissioned by Worksafe BC. What was their objective? And how did you translate their objective into an art installation?

Jill: Yes, so the original objective of WorkSafeBC was to create a memorial to acknowledge the workers that had been injured or had died in the course of their occupation, as well as a recognition of the increasing role that WorkSafeBC has had in worker safety over time. The commission I was initially awarded was anticipated as a two-dimensional work on the handrail of the pedestrian pathway west of the Vancouver Convention Centre.

However, as I engaged more deeply with the project and the site, I began to realize that there was a more spatial and interactive possibility for this artwork which had the potential to become much more three dimensional, as well as an opportunity to tell a more optimistic and comprehensive story about work in BC. Through discussions with the client representative from WorksafeBC, we decided that these important stories of workplace injuries and deaths could be told in didactic plaques near to the artwork but that the artwork itself could take on a larger story about work in BC- the potential to commemorate the past, present and future of work that could encompass all parts of the province, different demographics, genders, ethnicities and categories of occupations… as well as providing an optimistic view of the future.

Alberto: I guess a lot of work went into analysis of archival records. Can you tell me more about how and where did find all these information?

Jill: Sure. So as I mentioned previously about the more spatial opportunity for the work, I began to engage with the triangular piece of the green roof on the eastern edge of the pedestrian path rather than considering the handrail. This site offered a piece of land that started small and then grew as it reached out towards the water, which to me also reflected the changing landscape of work possibilities that exist in our province as one considers the small range of occupations possible in 1860 to the myriad of possibilities now.

The idea developed to imagine elements that reached out increasingly further from this sloped landscape to gradually arch over more and more of the pedestrian pathway – an idea of the increasing possibilities for occupations in BC over time as well as the increasing protection that WorksafeBC has provided over the province’s history. The work was roughly divided into 17 elements – 1 for each of the province’s 15 decades from its origin to the present, as well as one prior to BC’s establishment as a province and one for the future beyond the installation of the work.

I wanted to represent the general shift of work in the province form being land-based, to machine-driven to more human-centered and digitally based. A great range of different sources were consulted to develop this information matrix such as the National Employment Matrix, labor statistics, work statistics from WorkSafeBC, UBC libraries, BC Heritage Center documents, and a lot of other archival information to really begin to understand the cultural shifts that occurred in BC and within the world at large and how they affected work possibilities.

Categories were developed through this research and then occupations were filled in as we went. We began with the category of “subsistence”, then moved into other categories such as resource extraction, agriculture, infrastructure, forestry, etc. Each new category opened up new occupation possibilities. Important events such as the first and second world wars also changed occupational history in the province greatly so we wanted to reflect that as well. Over time, a large matrix was developed of rough categories and very specific jobs that became possible as related to these shifts. From here we went through a large process of culling and refining to decide which occupations to keep and which to let go of. The goal was to try to be as broad and all-encompassing as possible to reflect all the kinds of jobs that were possible throughout BC for all people. We wanted to have a collection of occupations that included those that were recognizable and perhaps relatable to everyone in terms of their own history or their family history but also to include some of the obscure occupations that might send people to Google to investigate.

Alberto: Well, this is incredible. How long did it take to go over all those archival materials?

Jill: Quite a few months actually, I think I would say four to six months. It was a big undertaking, but so interesting to dive into. I really enjoy the aspect of research in my work

Alberto: Despite the great transformation in the economy of the city, did you find something that remained constant throughout Vancouver’s history?

Jill: I think the thing that is constant is how occupations reflect cultural and global shifts as well as the particularities of the landscape in which Vancouver is situated.

Alberto: Now, if I may, I would like to ask you a couple questions about you and your work as an artist. I’ve always been interested in the professional lives of artists because, in the wake of the cultural revolution of 1968, artistic work came to be seen as the embodiment of “authenticity and freedom” , as opposed to the alienating dynamics of traditional forms of employment, of which the assembly line and the cubicle became quintessential representations. Can you tell me about the motivations or life events thal led you to become an artist?

Jill: I think being an artist does allow a certain amount of authenticity and freedom as you mentioned as one is able to the most part create and develop ideas that one is interested in, generally independent of the agendas of other people and systems. However working in public art, I believe that an artist has a responsibility to create works that tap somehow into the collective experience, not just our own personal motivations. Art in public space is usually in place for decades so has to somehow have resonance over time and for many different people, including those who see it every day and those who only see it once. That, as well as all of the practical constraints of building safe and robust works that will last this long, takes some of the “freedom” away from being an artist. “Authenticity” however is something that any good piece of art must maintain, regardless of its setting and constraints.

Alberto: As someone who has always and only “consumed” art, as someone who sees only the final result of the artistic process, I’m interested in learning more about the work of being an artist. Can you share with me what are the most rewarding aspects of your job, and also what are some of the least exciting aspects of being a public art artist?

Jill: I love the chance to create works that can start to change the way people think about spaces, themselves and their City, and seeing the different ways that works I have created change in use and meaning over time is extremely rewarding. I feel incredibly grateful to be able to work as an artist as my occupation. However, getting commissions for works is incredibly challenging and competitive and can often be heart-breaking. For public art, most works are commissioned through a competitive process that asks for artists to put all of their creative energy into the development of concept proposals which are then reviewed and selected by a juried process. So many ideas that I have invested in with my whole heart and soul never get built which can be very disappointing and exhausting.

Alberto: To conclude I’d like to try to look into the future. The 17th and last cantilever of Lines of Work describes a city which has entered in the post-industrial era as most of the jobs are in knowledge-intensive industries. How would you like the 18th cantilever to look like? In other words, how do you see the future of work in Vancouver?

Jill: It is going to be interesting to see the effects that the current pandemic and movements such as Black Lives Matter will have on the occupations of the future. With the pandemic – an acceleration of digital platforms for communication and ways of working have proliferated at the expense of in -person and tactile experiences. I wonder if that will continue or if there will be a big swing back the other way when the pandemic is over. I also wonder if we are starting to think more about the world at large and the fact that our singular actions can have effects on the planet and on other people far away from our immediate experience. It will be interesting to see what effect these cultural shifts will have on our occupations in the future.